Baseball once claimed the prime sports real estate where literature and movies construct allegory and metaphor. We feel NBA basketball, like a young ambitious developer striding into the urban landscape with high rises, office buildings and more, could seize that territory. Take the current NBA finals featuring the Los Angeles Lakers against the Miami Heat. The Lakers feature two superstars which might be enough for the team to claim the title. Compounding their good fortune, however, is LeBron and Anthony Davis have the establishment behind them. The NBA is the only sports league in which officiating is so biased towards its superstars. It’s not enough that these two players have such amazing athletic and mental gifts, they also get the benefit of the calls. Breathe on either one as they prepare to take a shot and a foul is called.

Raja Bell tells the story of playing against Kobe Bryant back in the day and just before the game started Kobe told the ref, “Call it even tonight.” In other words, Kobe wanted to take down Bell without the superstar refereeing advantage he usually was given. This phenomenon, which again does not exist in any other sport, is driving us away from watching the NBA. It drives us to foil the same phenomenon taking place in society where superstars also get all the calls, whether companies, institutions or people. But we always call them as we see them, based on data and information, including assessing China’s climate change pledge, ranking the elite of each country, and grappling with Vietnam’s challenges. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, the flyswatter of international e-newsletters.

In our continuing effort to keep your spirits buoyant, this week we present a snowball fight from 1896, colorized and speed adjusted.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

China Climate Change Pledge

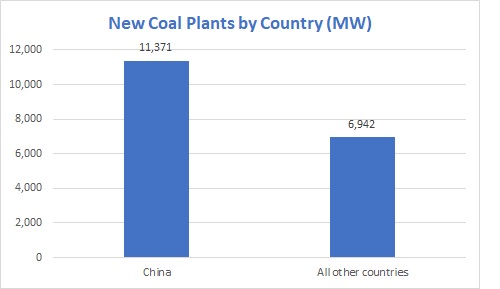

A few weeks ago, during the United Nation’s General Assembly, Xi Jinping gave a speech via video (but not a 15-second Tik Tok video). In it, he stated, “We aim to have [carbon dioxide] emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.” Among those who paid attention, many trumpeted the carbon commitment as a huge step in fighting climate change. Others were skeptical noting that China continues to build coal generating plants at an astonishing rate: “In the first half of 2020 China approved 23 gigawatts-worth of new coal power projects, more than the previous two years combined,” reported the Singapore Strait Times. As New York Times reporter Mike Forsythe notes, “that is 10% of TOTAL US coal power capacity that China approved in just 6 months!” So is Xi’s statement a big deal or mere propaganda aimed to enhance China’s standing in the world? As with most things in life, it is probably not just one or the other. Xi certainly has and will make commitments that put China in a better light that he has no intention of fulfilling—that has certainly been the case on opening up its economy to international competition. But if progress on renewable energy generation, storage and other technologies continue at their current pace, we expect China’s 2030 and 2060 pledges are fully doable. If such technological progress is not achieved, then China won’t meet its carbon reduction commitments. In this case, the key is not whether to trust Xi or not, but to enact policies that make these technological breakthroughs more likely. We recommend such policies in our upcoming book

Whose Elite are Elite?

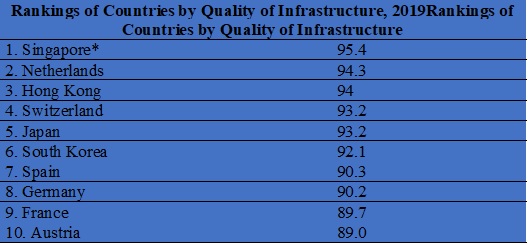

The modern abundance of data has given rise to the desire to measure everything, including, we discovered last week, the elite. Yes, that much disparaged group of people who have the most sway over the countries in which they live, are now under the data analytics microscope. The Elite Quality Index was developed by the Foundation for Value Creation which asserts that the elite are a certainty, they supply essential coordination capacity to societies, and the quality of the elite in a country determines the country’s economic and human development. We are still plowing through the Foundation’s methodology but essentially the index places a high premium on those elites who work to create value rather than extract it. The index is very concerned about rent seeking where the elites “increase their own slice of the (economy’s) pie at the expense of the non-elites.” So which countries have the best elite? The Elite Quality Index ranks Singapore number one but after that quasi-democracy, city-state, the rest of the top ten are all democracies representing three continents: Europe, North America and Asia. China, at number 12, is the first true non-democracy on the list. In our upcoming book, which you’ll soon be able to pre-order, we cite the work of Yuen Yuen Ang, who quantifies the types of corruption in China compared to the U.S. and India and finds that though there is lots of corruption in China, it is of the kind that at least in the short-term, can have economic benefits. The Elite Quality Index appears to reflect Ang’s assessment. At any rate, check the list below so depending on where you live you can taunt, “Our elite are better than your elite, nyah, nyah, nyah,” which, of course, perhaps an elitist might not do, at least not in that manner.

The Promise and Challenges of Vietnam

Vietnam is one of the five most important countries in the world. And, so far, they have handled the Covid-19 pandemic almost as well as any country in the world and have consequently seen their economy perform better than most the last 9 months (or at least less bad). Vietnam has also benefitted from companies diversifying supply chains outside of China, which began before the pandemic due to rising costs in China. But, Vietnam has at least two big challenges to continue its economic rise. First, is improving and expanding its education levels. An article in the Asia Times Financial notes, “only 12% of Vietnam’s approximate 57.5 million workforce can be identified as highly skilled.” World Bank data shows Vietnam middle of the pack in terms of school enrollment. It’s second among ASEAN countries in the rankings of the human capital index and Vietnamese score high on international standardized education tests. There are not enough universities for all the students who want to attend them but Vietnam has certainly taken steps to increase the percentage of its population who are highly skilled. The other big challenge is infrastructure. Vietnam’s roads, port facilities and other infrastructure all need to be improved. On a scale of 0 to 100, Vietnam has a 65.9 score on infrastructure, which ranks it 79th behind countries such as Indonesia, Uruguay, Mexico, Turkey and other markets. Vietnam needs to concentrate on infrastructure over the next 5 years, as well as continue to improve its educational system. Countries such as the U.S. and Japan should help Vietnam in these endeavors.

*Note Singapore’s elite ranked high too—in fact there is much correlation between the elite and infrastructure rankings