As Seattle weather settles into an Alaskan spring of cold, clouds and drizzle (I love cultural appropriation but hate climate appropriation) excuse us a moment of ventilation. This week’s twin mass shootings driven by ethnic and racist hatred are reasons for despair and reflection. We lament that the Buffalo shooting forced us to learn a bit about Replacement Theory. There are sixteen thousand seven hundred and fifty four other concepts we’d rather have learned about. Our country has been productively replaced (if not always happily) since it’s founding, with successive waves of immigrants refreshing and building America.

As we wrote in Challenging China, relatively successful immigration is our country’s most distinctive and distinguished feature. America acted as a model of and force for freedom and democracy for the world the last 300 years. Despite our flaws and foibles, we could be a model this century of how multiple cultures and peoples from all over the world add to up a better whole. if we only are willing to do so. Irish, Italians and Jews were once reviled as much as today’s immigrants. Some of today’s most successful immigrant populations, economically at least, are Nigerians, Filipinos and Vietnamese, bringing new experiences, ideas and backgrounds to the country. Immigrants are far more likely to start a business and far, far less likely to commit crimes than native born Americans. A new wave is improving upon and building America. One of the flaws of America is its inability to create an environment that provides similar opportunities for Black Americans.

The American ideals that have made possible the success of immigrants, and thus the country, the ideals that so many of the Replacement theorists theoretically hold in high regard? They are not white ideas, whatever that means. America’s founding fathers expressed them eloquently and constructed a structure to put them into practice, setting the stage for a slow wave, that ebbs and flows, of freedom and liberalization around the world. But the ideas forming the basis of America were developed over the centuries, drawn from many cultures and continents, including from indigenous people in the Americas. These truths that for too many are not self evident are for and from all people. The great work of America for the 21st Century is to show it does not matter where you come from or what you look like but that it is possible to get to where you want to go. And we go to again defending global supply chains, examining the rise of Southeast Asia and wondering what was up during our meeting with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, putting on another sweater while bringing you hot takes on the world.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

In Further Defense of Global Supply Chains

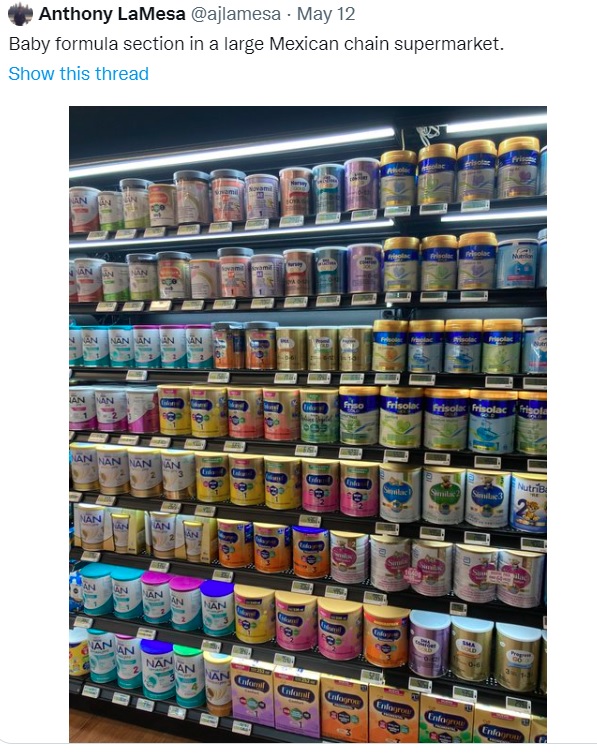

Last week we asserted we need to diversify global supply chains so that they are not so concentrated in China. And we do need to do that, but global supply chains have become the last refuge for policy makers, journalists and companies to distract attention from what are the real problems in shortages. Last week the supply chain blame topic de jour was baby formula. Headlines, including in our local newspaper, trumpeted the problem and blamed, you guessed it, supply chains. But when I read the articles it was almost all about a recall that took place at Abbot Nutrition’s Michigan facility. The reporter included a vague sentence asserting that ingredients were hard to find in the supply chain but did not offer a shred of evidence or data to back up the vapory claim. And as we dug into this more, it turns out the real problem has little to do with supply chains but rather policy and regulation. The libertarian magazine Reason has a good explanation of why we can’t import perfectly fine baby formula from Europe. Mexico’s grocery stores are chock full of baby formula as you can see in the photo below. Of course, before our libertarian readers leap up, hands reaching for the sky shouting praise the Lord* for this common sense, analysts on the left point out the shortage arises because we’ve allowed consolidation into only three baby formula companies in the United States and if we only implemented anti-trust laws we wouldn’t be having these problems. Of course, someone on the right might say our overabundance of regulations means only a few large companies can successfully navigate such an environment. Whatever your political predilections, the baby formulate shortage has little to do with supply chain problems. In fact, a big factor in the shortage is we’re not using global supply chains. The baby formula shortage is about bad policies not supply chain issues.

*Or is it Ayn Rand?

No snide remarks about our continuing to read a physical newspaper. If it’s good enough for Klay Thompson, it’s good enough for us.

The Rise of Southeast Asia

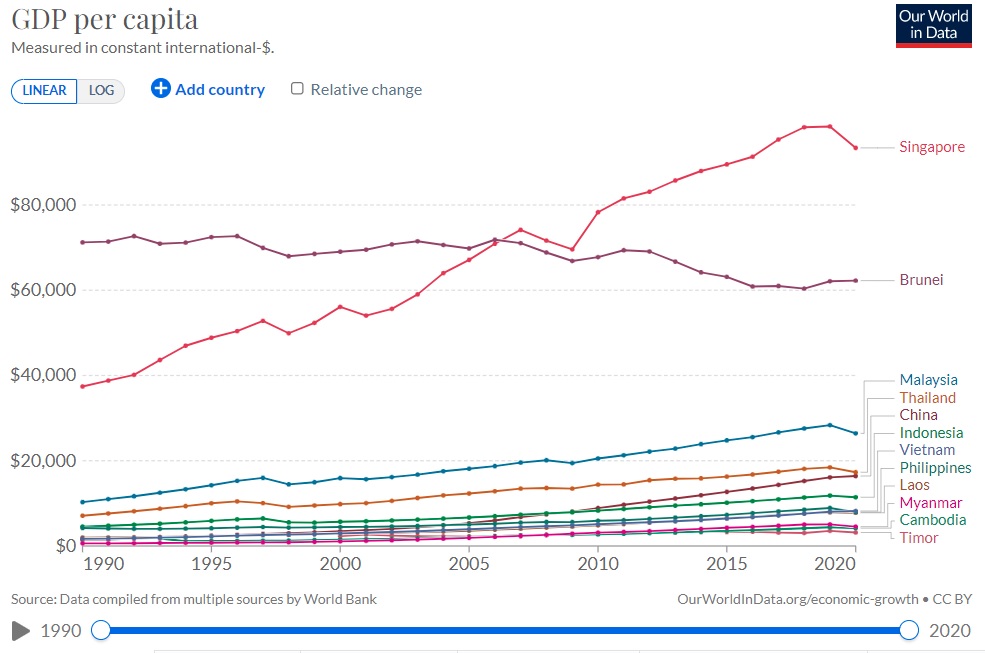

We’ve had plenty of opportunity to think about Southeast Asia the past week. We’ve been in meetings over Zoom with folks from Vietnam, discussed someone’s investment project in another nearby country and, of course, the Philippines elected another Marcos to be its president. There has been much understandable angst about the latter. It impelled us to look up GDP per capita growth rates for countries in Southeast Asia (plus we added China for kicks), which you can see below. As you can see in the second chart below, all countries in the region increased their GDP per capita over the decade from 2010 to 2020 but Vietnam was the leader with a 61 percent increase in GDP per capita, followed by Laos and Cambodia. The Philippines doesn’t fare so well by this measure although it has increased its GDP per capita significantly over the last 30 years after the fall of Marcos (perhaps with Marcos in place an increase in shoe production will up its GDP growth rates). Note that we stop the chart before the onset of the pandemic which has disrupted economies around the world. The next eight years will be crucial ones for all these economies. What Marcos does, what Vietnam’s communist party does, will drive what happens for the welfare of their people over the next decade.

China Corner: The Premier

China’s Premier Li Keqiang has been in the news recently, including a Wall Street Journal article stating he has been “stepping out of Xi’s shadow.” The idea is that Li is trying to influence policy to not be so rigid and to lighten the crackdowns on tech and other companies that Xi has launched in recent years. In general, Li has expressed concern about the state of the economy and appears to be pushing for a change of direction. We, too, have wondered if internal pressure is building against Xi, but, of course, there’s no way to understand what is happening behind the scenes and in the shadows of the dark inner circle of China’s leadership. But all the talk of Li as a counterweight made us remember when we met Li Keqiang almost ten years ago as the transition to Xi’s leadership was beginning. We had been invited to speak at an investment conference in Beijing, and along with other speakers we were invited to a small meeting with Li. Invitees sat in a set of concentric circles with the most important people—the CEOs of large companies (top of the Fortune 500 large) in the circle closest to Li. We, not being important at all, were seated in the outer third concentric circle next to a State Department functionary and lower level corporate staff member. They both were fluent in Mandarin. Li arrived quite late, which was unusual for him, especially given the status of his first circle guests. And he seemed a little off, which even we could notice, who is most certainly not fluent in Mandarin. Li even appeared to be sweating, literally, not figuratively. He spoke a bit hesitantly and said a few strange things—at this distance to time, we don’t remember exactly what. Afterwards, after the requisite handshaking and formalities, Li quickly left the room and my two seatmates wondered what was up: was something going on in the leadership transition? So, today, we ask the same question: what is up?