We see people getting mad at and attacking others all the time on social media, in comments sections of websites and elsewhere. Humans are quick to judge others, their intentions, their characters, their entire lives based on a small moment—whether a tweet, a comment, an opinion, a discrete action. We are as guilty of this as anyone else (though we usually refrain from judging online, the thoughts still infect our head).

We ponder this because on Twitter, believe it or not, we saw someone refrain from tweeting a withering response to someone who had rudely replied to their tweet. They refrained because before responding they first examined the rude responder’s timeline and realized the person had been going through some tough times. Another person, a China expert who we follow on Twitter, replied with this quote by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.” It’s a good quote not negated by the fact this China expert often leaps at the opportunity to judge others on Twitter.

This interaction made us recall an old college acquaintance who years ago friended us on Facebook and whose posts revealed he had some pretty repugnant views of the world, and certainly was too far right for our tastes. It made us, we admit, think lesser of the person, whom we never held in particularly high regard to begin with. But one day he posted about the death of his brother, who we also knew back in the day. Except his brother had transitioned to a woman a number of years ago, something we did not know until his brother’s Facebook post about her death. This old college acquaintance wrote lovingly and eloquently of his now sister, calling her the bravest person he knew. We never would have guessed he’d do so based on his multitude of reactionary Facebook posts over the years. But he, and we, and you, contain, well, multitudes. And we bring you if not a multitude than at least some key stories on Covid’s complicated lessons, the possible myth of the democracy deficit and China’s GDP BS. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, nominated for 11 international data and information Oscars.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

Wait, What About Covid?

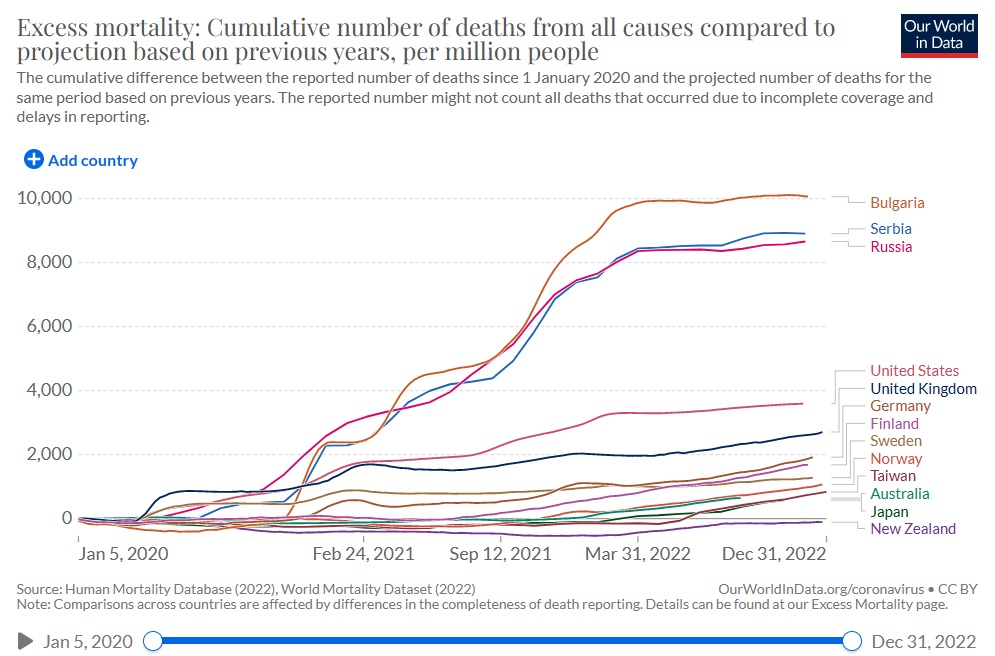

Whether a guy in a bar in South Texas or a woman shopping in a mall in Guangdong Province, most of us have moved on from the pandemic, even if the virus hasn’t moved on from us. But as we reach three years since the first known cases of Covid began infecting people in Wuhan, how did countries do in managing the pandemic? One measurement to look at is the number of excess deaths in each country. Since each nation’s criteria for counting Covid deaths is different (in China they are actively encouraging doctors to classify deaths as just about anything else other than Covid), examining excess deaths might give us a better idea of the number of Covid deaths in a country since January 2020. As you see in the chart below from Our World in Data, for the most part it’s difficult to say which countries’ policies did best during the pandemic. Certainly New Zealand, as its outgoing Prime Minister will certainly trumpet, did well. Most countries who dealt with SARS back in the early 2000s did better in handling Covid than those that did not. Early on some praised Sweden’s less onerous restrictions and then as their cases sky rocketed Swedish policy makers were castigated. But after three years, Sweden did a little bit better than its neighbor to the west, Norway, and a little worse than its neighbor to the east, Finland. All in all, these results and other measurements should make all of us humble about our analysis and predictions over the last three years. But we predict it won’t.

Is There Really A Democracy Deficit?

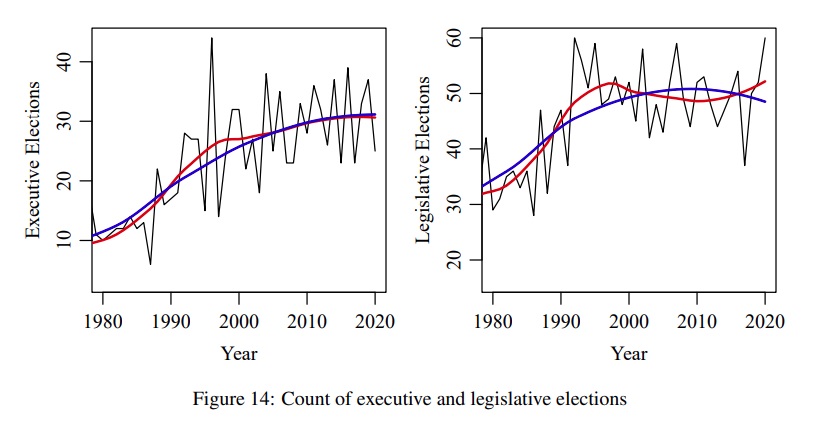

Over the last decade many folks have posited that democracy has been backsliding in the world. Freedom House, for example, asserted in their Freedom in the World 2021 Report that “the global decline in democracy has accelerated.” But a new study by Anne Meng and Andrew Little with the incredibly exciting title, “Subjective and Objective Measurement of Democratic Backsliding” takes issue with these assertions, or at least claims it’s more complicated. The paper looks at “objective” measurements such as incumbent performance in elections and frequency of elections, and finds that there has not been backsliding in democracies around the world.

The rate of leader and ruling party turnover has remained fairly constant since the late 1990s. If anything, the vote shares of incumbent leaders in executive elections and incumbent parties in legislatures have decreased in recent years. We also find no evidence that there are fewer elections with real multiparty competition.

The study also asserts that previous assertions that democracy is on the wane are based on subjective measurements. However, if we are reading the paper correctly, the authors examine the democracy issue by number of countries. Other analysts, such as Freedom House, do so by examining the number of people living under a democracy. In the latter analytical prism it really comes down to how you view what is happening in India the last decade. If you believe it has become un-democratic under Mohdi, than indeed there are 1.4 billion people no longer living under a democracy (about 17 percent of the world). If you are looking at the 200 countries of the world, well, India is just half of one percent. As to whether India is no longer democratic, we don’t understand the country well enough to adjudicate the argument, but we are working to. At any rate, this new paper might make people more hopeful about the state of the world the last ten years. We bet it won’t though.

China Corner: The BS in CCP GDP

There is no “I” in “team” but there is definitely “BS” in GDP, or at least in China’s. China is claiming 3 percent GDP growth in 2022 and 2.9 percent growth in the fourth quarter of last year. Neither are believable. Let’s take a look at China’s claims of 2.9 percent growth in the fourth quarter of 2022. Chen Long of Plenum China points out, “nominal household consumption dropped 2.4% yoy in Q4, so the yoy decline in real terms was probably 4-5%.” We could point to lots of other underlying data that makes it difficult to believe China grew 2.9 percent in the fourth quarter. Meanwhile, China Beige Book, which tracks activity in China, believes China likely grew between 1 and 2 percent last year. That’s more believable. It’s also in line with what we’ve been predicting: going forward China’s economy will grow at about the same rate as the U.S. and Europe with all the ramifications that come with that. This year China will experience bounce back growth from eliminating its Zero Covid policy (though maybe not as much if they use a fake baseline built on 3 percent growth for last year). But after that, China growth will be low due to aging demographics, less productive debt, lower productivity, the real estate hangover and other challenges. GDP is just one data point among many that China is not transparent about. We hope they’ll be more transparent in the future but we predict they won’t.