There are two types of people in the world (there’s actually 8.1 billion types of people in the world but that’s a discussion for another day): those making fun of AI’s shortcomings and those using it. We’re in the latter camp. We use it every day, mostly the paid ChatGPT4 version. We certainly use it for work, sometimes deploying it to write boilerplate stuff that we don’t have time for, sometimes using it to create the foundations or outlines of projects we’re launching, sometimes to analyze data and sometimes to create images. It not only saves us time but improves what we work on. We also use it in our personal life, including in helping create itineraries for vacations.

AI has arrived in the nick of time—search engines, including and especially Google, have become nearly useless. The information I get when typing in a prompt into AI is significantly more usable than the riff raff of ads and strange priorities Google provides. And people are using AI to create all sorts of cool tools, from customer service that apparently is more reliable (we’re working on Please Hold 2—Revenge of the Nerds) to medical advancements to other applications. One guy I was talking with recently told me his company after implementing AI eliminated 40 percent of its workforce in India. Uh oh, that is actually worrisome. But most people’s jobs won’t be replaced by AI (until and if we achieve general AI), they’ll be replaced by people using AI, probably including the people wasting their time making fun of AI’s shortcomings.

I was fortunate to make a trip to Maryland last year to see my Uncle John. Many, many years ago when I lived in Washington, D.C., John and I occasionally played racquetball. I can’t particularly remember who usually won which likely means he did, despite the fact he was much older than me. John was kind and fun to talk with and also stubborn. I had taken the subway and bus from meetings in D.C. to see him last year but after our visit he insisted, despite his Parkinson’s, on driving me to the metro station. He really shouldn’t have been driving at all and I’d be lying if I said my heart rate didn’t elevate at least a bit during the drive. But not because he drove badly but because of my worry about his driving at all. John was nothing if not competent—in his time in the military, in his work at Mitre, in being a loving father and husband…and as an Uncle. RIP.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

Japan Is Fab for Fabs

In a speech earlier this week to the Bellevue Rotary about China we talked about how every single fab plant that was announced after Congress passed the Chips Act is delayed—from TSMC in Arizona to Intel in Ohio to Samsung in Texas. This is in large part due to America’s bad regulatory regime and sclerotic bureaucracy. But you know where it’s possible to build semiconductor plants efficiently? Japan. Last week, TSMC—the Taiwan semiconductor giant—opened its first semiconductor plant in Kumamoto, Japan. And it announced it will be building a second plant in Japan. A Bloomberg article quotes the author of Chip War, Chris Miller as saying, “The contrast between TSMC in Arizona and in Kumamoto is quite striking,” It is indeed. As we said in our speech in Bellevue, we can restrict the transfer of technology and the sale of semiconductors and other strategic products to China all we want but it won’t matter unless we can develop and build the technology ourselves. But we amend that statement here. It’s good if Japan and other allies are building these sophisticated semiconductors. Keeping strategic industries safe outside of China is a global endeavor not an American one. Still America needs to reform its regulatory environment.

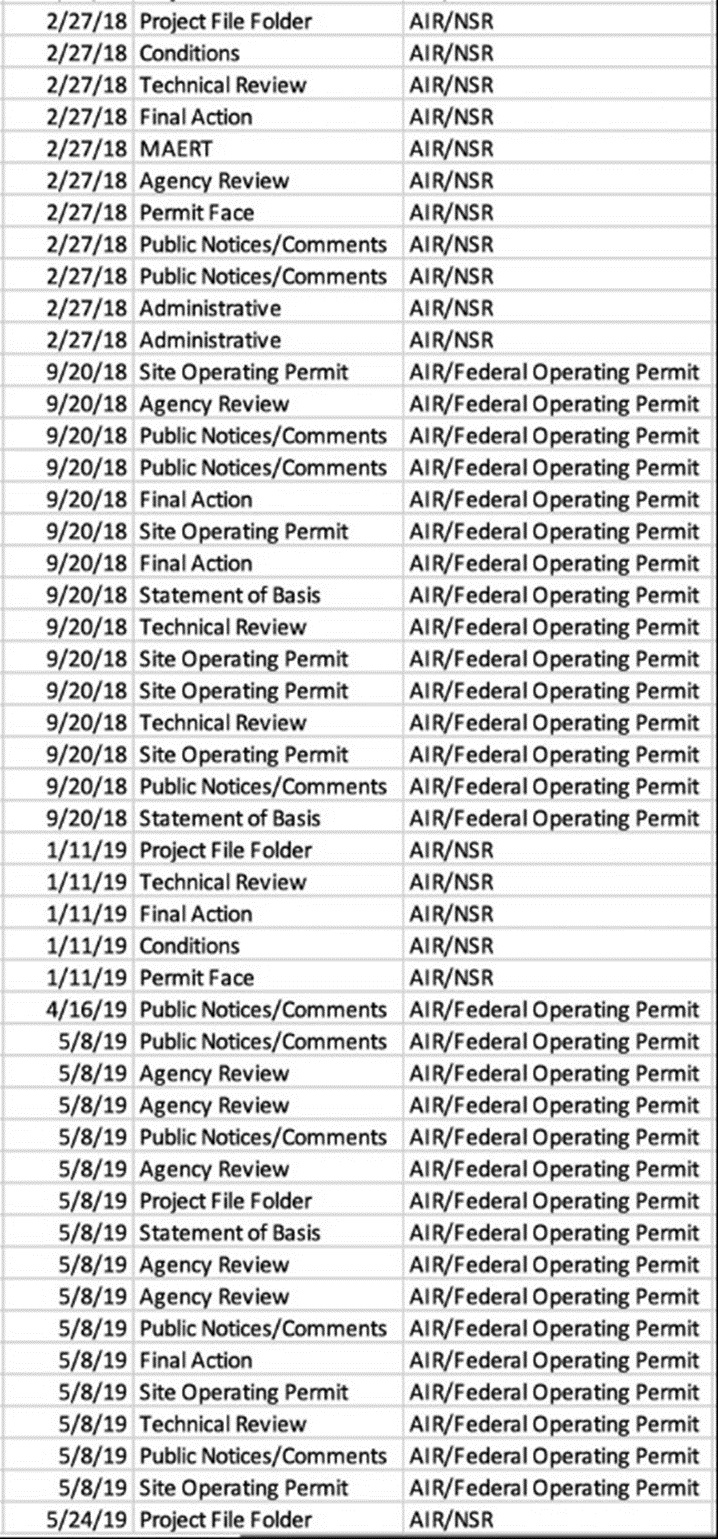

What is this? Why am I making you look at something so ugly? It is the list of permits/applications/reviews for Samsung’s chip plant in Austin, Texas. This only represents the permits under the Clean Air Act’s New Source Review program. It doesn’t include all of the other permits, applications and reviews Samsung must go through to build their fab plant

The Wealth of Nations

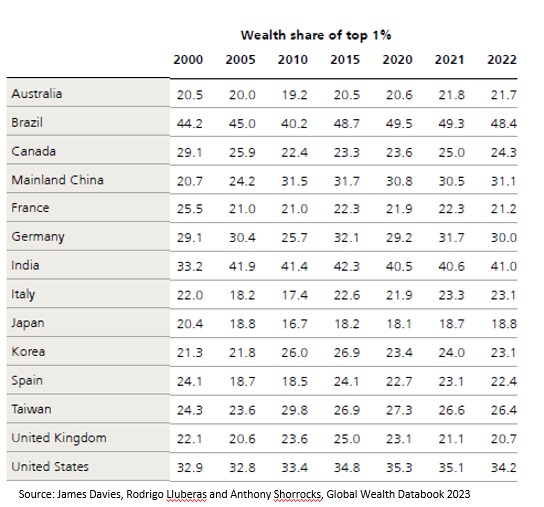

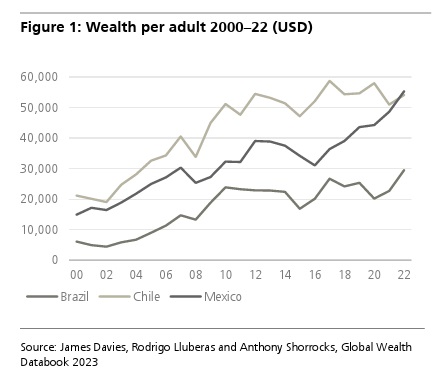

As we perused UBS’s 2023 Global Wealth Report (what are you doing in your spare time?) we noted that there are other countries with even higher concentrations of wealth among the rich than the U.S., which is saying something. The wealth share of the richest one percent is 48.4 percent in Brazil and 41 percent in India. In the U.S. it is only 34.2 percent—c’mon ultra wealthy Americans, get your act together. China is 31.1 percent. We already knew how unequal China was but were a bit surprised just how much India and Brazil are. Germany is up there, too, at 30 percent, which might be a function of its supporting its exporting companies to the neglect of its workers. Speaking of Brazil, Mexico’s wealth per adult recently surpassed it thanks to strong economic growth in recent years. In fact, Mexico’s GDP per capita is much higher than Brazil’s. With lots of investment flowing into Mexico, including from China, Mexico’s economic fortunes are looking good.

China Corner: Democracies Diversifying

China analysts love to talk about “decoupling” like a bunch of greedy divorce lawyers. It’s almost always framed as the U.S. decoupling from China but in reality China began the decoupling years ago through its dual use policy, recent efforts to make everything themselves, and even the Great Firewall built years ago. And more accurately what’s happening recently is the U.S. is diversifying its supply chain, not decoupling. But of course it’s not just the U.S. and China, it’s a number of countries who are looking to diversify their supply chains as a recent article in Forbes reports. Germany’s imports from China have recently decreased and in fact preliminary figures show the U.S. may now be exporting more to Germany than China. Plus, “Japan and South Korea have also disengaged from China, at least to a degree.” All of this is based on preliminary data and trade data is too often simplified–as we’ve been saying for years international trade data is in need of a sabermetrics revolution a la sports data. But it would not be surprising after China proved unreliable with its Zero Covid policy and with its aggressive foreign policy that many democratic countries are hedging their bets on where to source stuff.