One of the great moviegoing experiences of our life was seeing Pulp Fiction opening night at the Neptune Theater in the University District of Seattle. By opening night, we had seen on video Tarantino’s first film, Reservoir Dogs. The year before, we saw True Romance in the theater, a movie Tarantino wrote but did not direct. We loved both of these films and the excitement to see Pulp–which had won the Palme d’or at Cannes and in the pre-Internet-information-is-sparse era was building a legendary aura–could not have been higher. The theater was packed and our recollection is the crowd cheered as the movie began to play. And when the opening credits came on after the electrifying opening diner scene with Dick Dale’s Miserlou roaring on the soundtrack, the crowd could not have been more pumped for Pulp. The incredible Samuel L. Jackson soliloquy, the Travolta-Thurman dance sequence, the unbearable tension of the needle scene—the whole film lived up to the hype. Our experience was amplified by a few of our friends walking out of the theater in disgust during The Gimp scene, which made us revel in the rebel movie all the more.

So, when we had the chance last week in this, its 30th anniversary year, to revisit Pulp Fiction on the big screen we jumped at it. This time time we saw it at the Grand Illusion, also in the University District–a tiny theater with a screen not much larger than what you’d find in a wealthy person’s home theater. But the crowd was excited nonetheless. We were surprised that we were by far the oldest person in the movie theater and that women made up nearly half the crowd. Pulp Fiction, three decades later, still resonates with youngsters. And it still holds up. A perfect movie—we were jealous of those in the theater seeing it for the first time. So, without furious anger or great vengeance, we bring you three stories about manufacturing—the realignment of autos, where robots are rising and China’s dominance. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, stuffing stockings with global data, lighting menorahs with international information.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

World Wheels Realigned

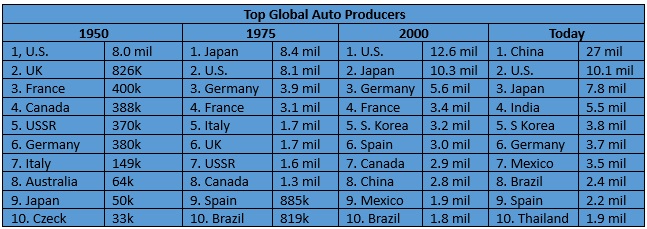

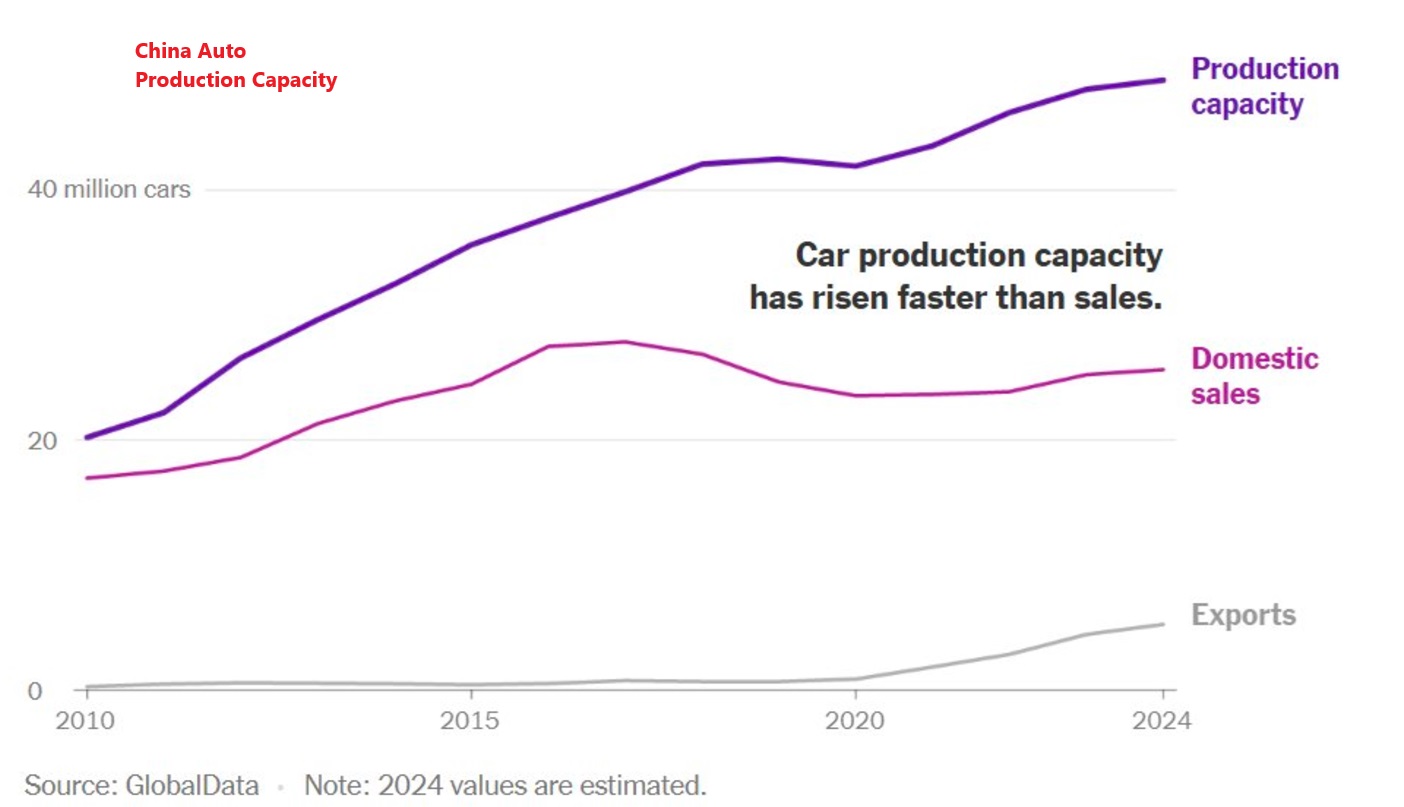

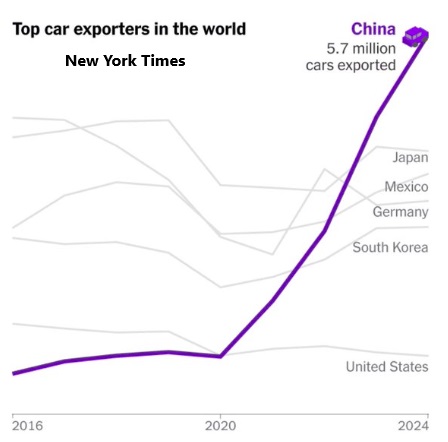

In doing research on countries’ share of global manufacturing we stumbled on the remarkable statistic that in 1950 American car companies produced 75 percent of the world’s automobiles. Countries ravaged by the war were still rebuilding allowing American companies to rule supreme, presumably an Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme.* But as Japan and Europe rebuilt, auto building spread more evenly. And then South Korea rose and Mexico too. But now there’s a new sheriff in town and China’s rise in auto manufacturing, as in so many other products, is stunning. China became the largest producer of autos in the world in 2007, just barely ahead of Japan and the U.S., as you can see in the chart below. Today it produces nearly four times as many as Japan and nearly three times as many as the United States. Fine, you say, China is a much larger country than those two, so it should produce far more and they are mostly low-quality cars for the domestic market. But this year China became the largest auto exporter in the world and its new EV cars win rave reviews. Japanese car companies, including Nissan, are in big trouble. At what percentage share of the global auto market will China peak? Presumably they will not reach 75 percent. Right?

*That short post-war era has damaged U.S. policy thinking for decades—everyone wants to return to a 1950s economic era that was anomalous. The U.S. was doing so well and so dominant because so many countries’ infrastructure and economies were destroyed during the war. The only way the United States returns to such an economy is if we dump a bunch of bombs on the industrialized world, a strategy we most certainly don’t recommend.

Notice, btw, that often countries aren’t producing less cars over time, just that others are producing even more. Kind of a win-win situation in many ways.

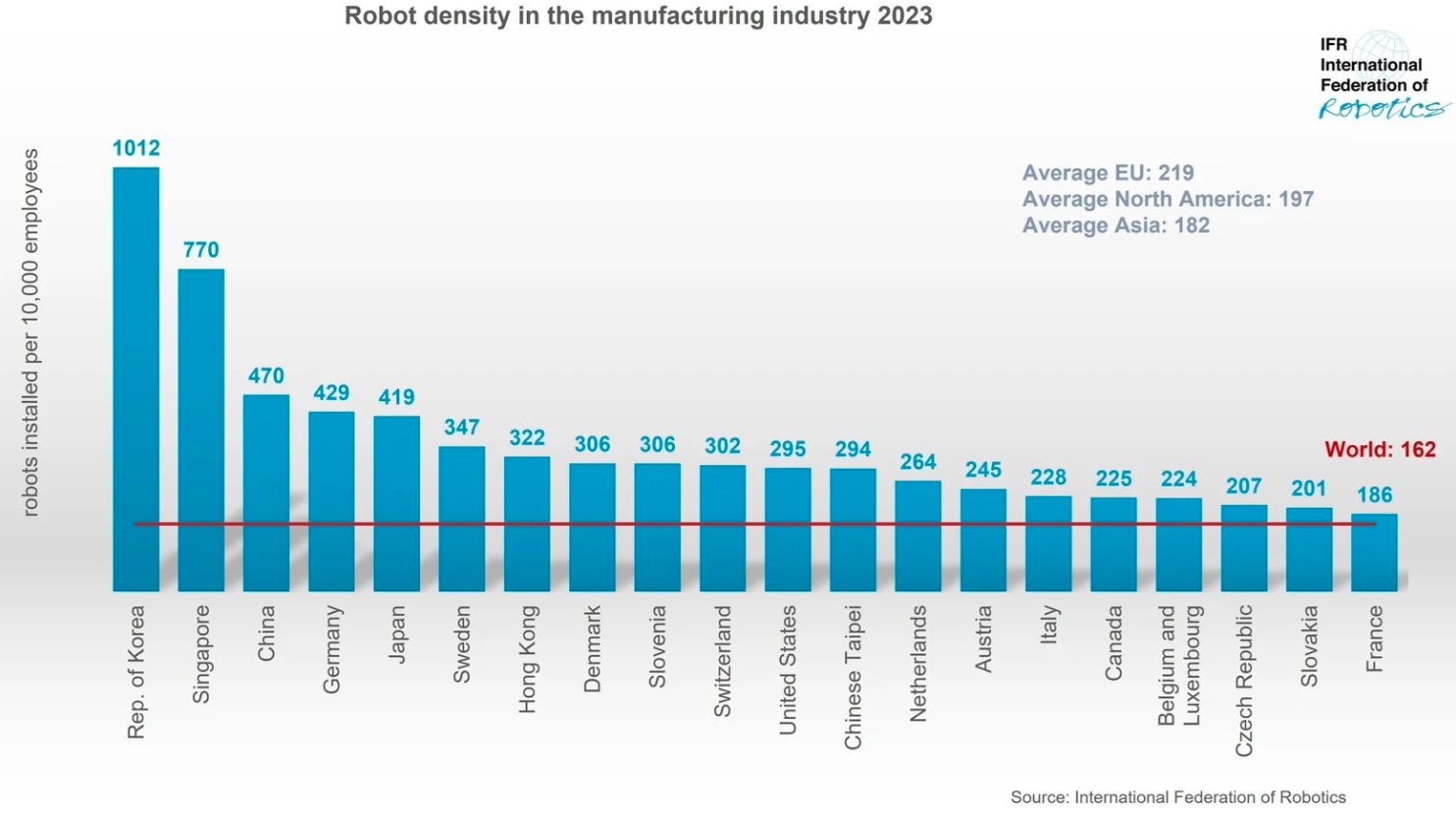

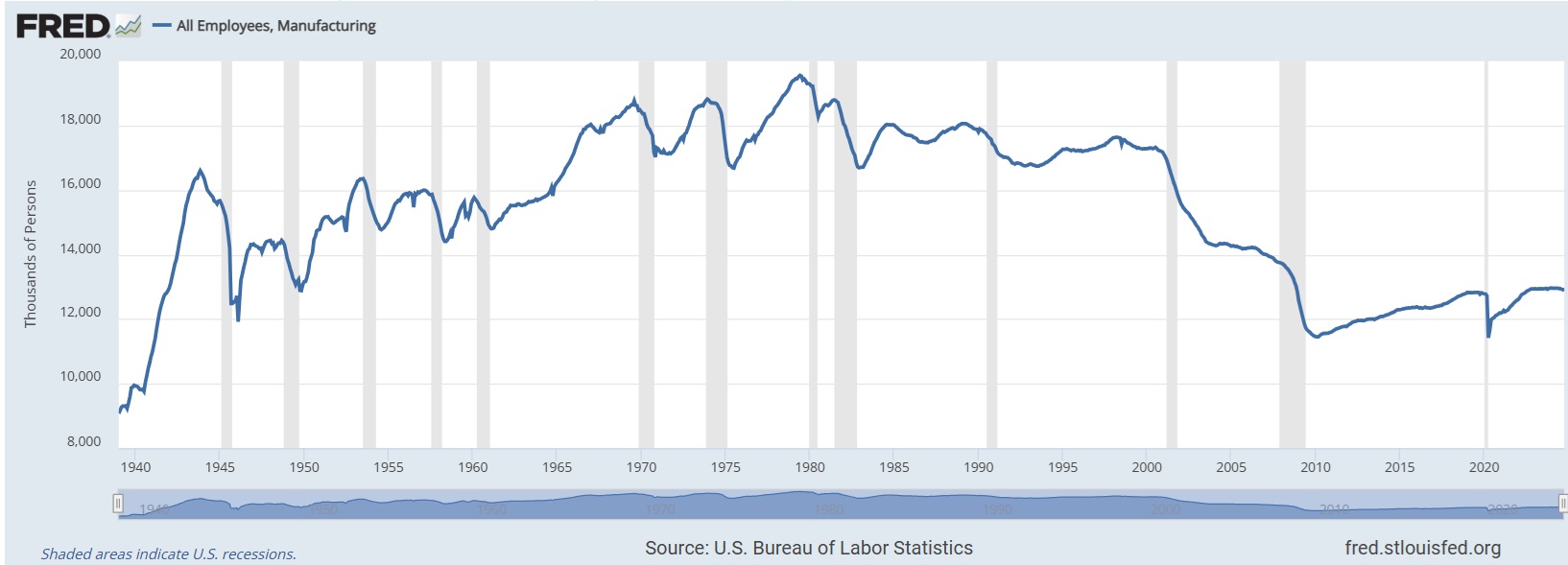

Follow the Robots

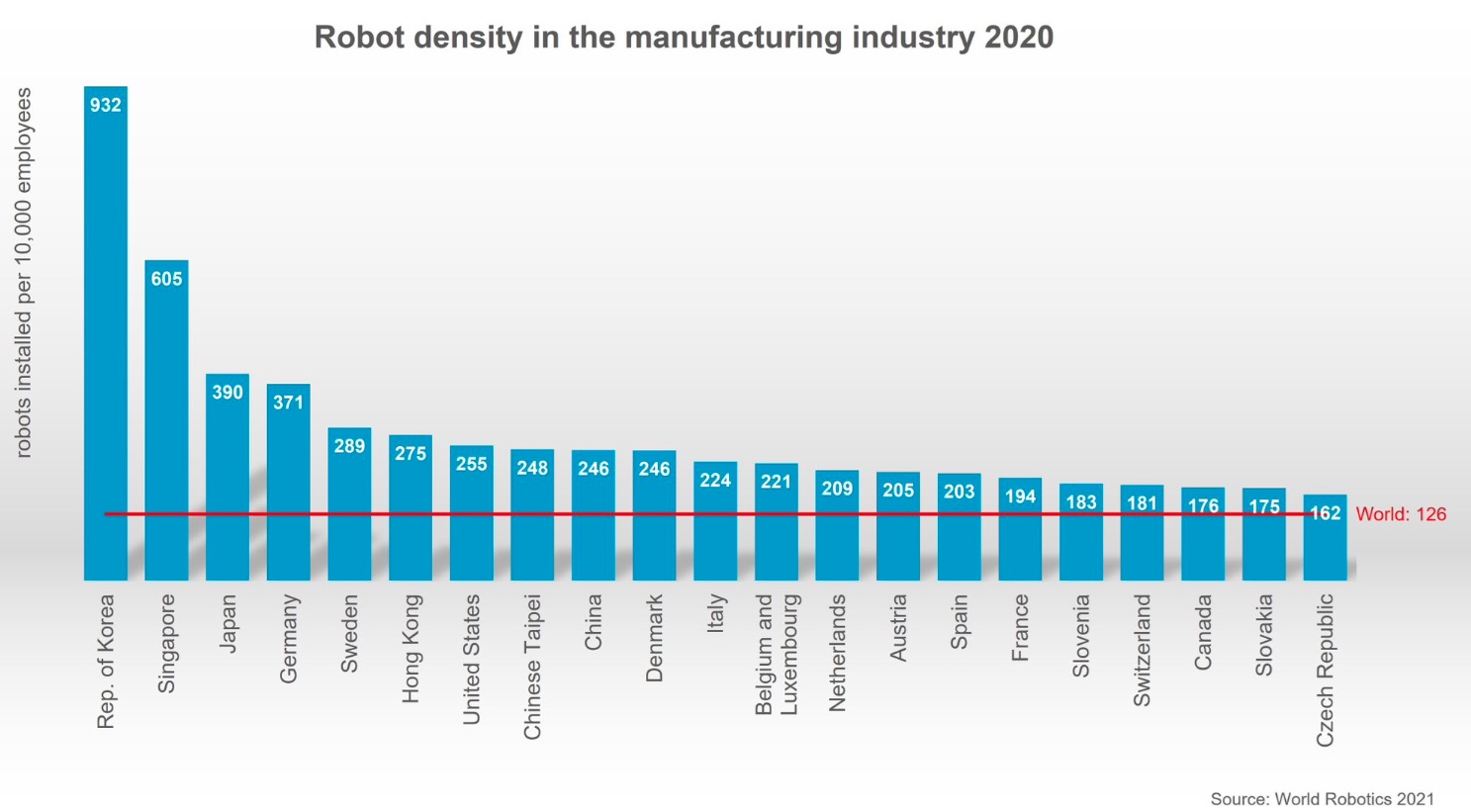

Politicians often frame manufacturing policies around increasing jobs, but the world is producing more goods using fewer people. The Biden administration rightly tried to attract more manufacturing with some success but it did not lead to more jobs. That’s partly because of automation and partly because of the increased use of robots. To see where things will be built in the future, don’t follow the money, follow the robots. The International Federation of Robotics gives us a glimpse into the future. As you can see in the two charts below showing robot density in both 2020 and 2023 in the manufacturing industry, South Korea continues to dominate. But notice in those three years that China has gone from 246 robots per 10,000 workers to 470 robots per 10,000 workers, a 91 percent increase. The United States, by comparison, saw a 16 percent increase. South Korea* saw only an 8.5 percent increase but was starting from a large base. China, as we quantify below in the next story, is the factory of the world, and aims to stay that way. But don’t assume more and more Chinese will be employed in manufacturing. It is no longer a job producing sector.

*We had not expected to wake up earlier this week to news of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol trying to pull a North Korea. As we wrote last month, this is the era of living dangerously. Thankfully, South Koreans resisted the power grab. Let’s hope democracy continues to win battles around the world.

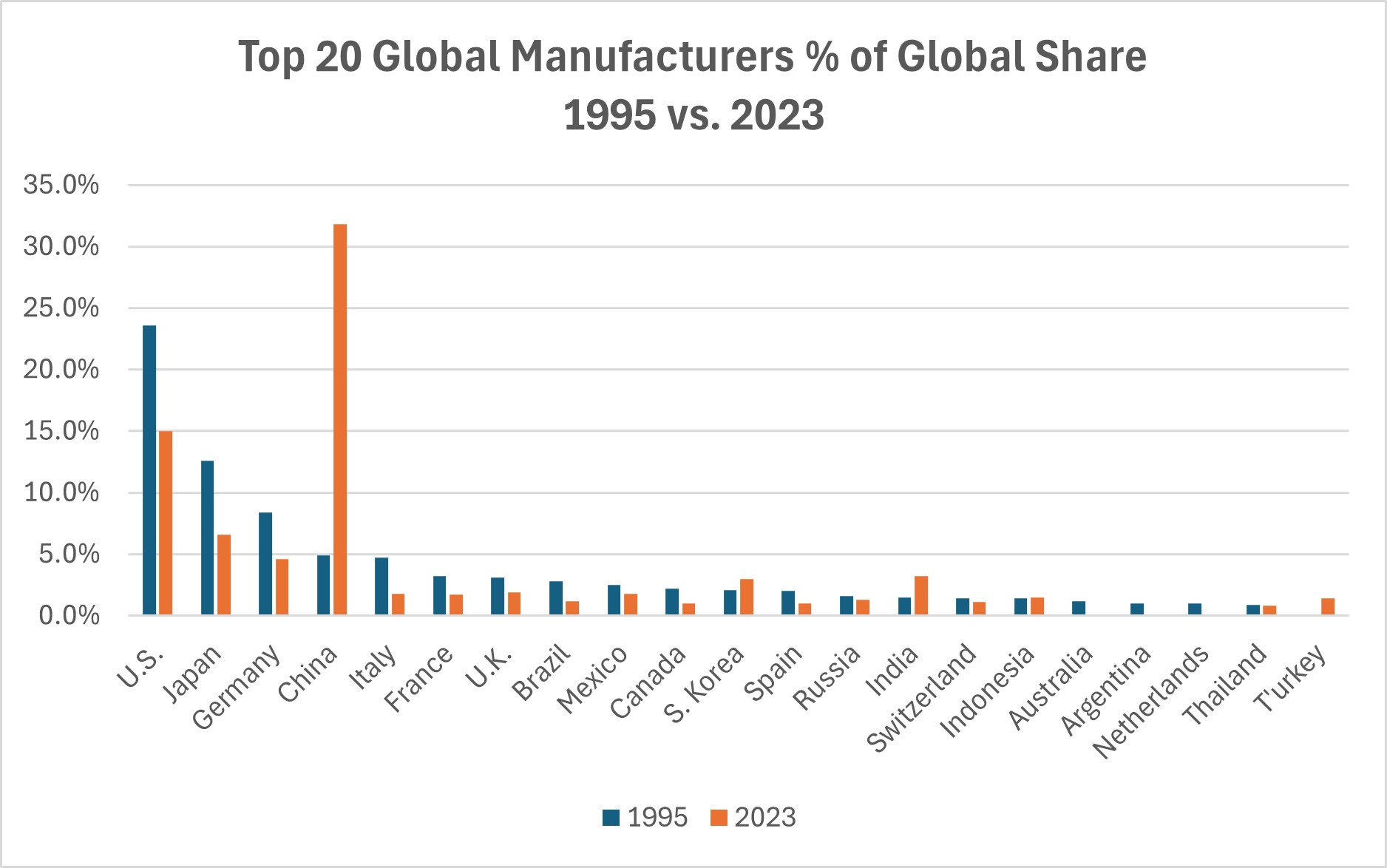

China Corner: The Worlds’ Factory

It’s been much commented on, including by us in a book, articles and presentations, but China’s economic rise and dominance continues to stun. We recently perused, as one is wont to do during the Thanksgiving holiday, the UN’s International Year of Industrial Statistics. It is chock full of interesting data on manufacturing around the world. What stands out is China’s rise in share of global manufacturing since the 1990s. In 1995, as you can see in the chart below, the United States accounted for 23.6 percent of global manufacturing. Japan–remember their dominance?– was second at 12.6 percent, followed by Germany (8.4%), China (4.9%) and Italy. But today, China captures 31.8 percent of global manufacturing. Not only did China pass the United States, but its share is also higher than America’s share in the mid-90s. We guess that in 1950 the United States was at least that dominant in global manufacturing, though we are unable to find any data from back then (only global auto manufacturing—see the first story). Today, the U.S. is second but at only 15 percent. Japan is down to 6.6 percent and Germany to 4.6 percent. But hark, a new country is on the rise: India is now fifth at 3.2 percent. We wonder if, by mid-century, India will be number one and just how dominant it might be. Or will manufacturing be spread more evenly throughout the world in the coming years?