We first got onto Twitter in August 2012. We are often an earlier adoptor of certain types of technology but we resisted Twitter because we were intrinsically against the brevity of its content. We were one of the first readers and writers of blogs because it was one of the best ways to learn about our world. Likewise podcasts. As a Seattle Mariners fan, we jumped on the early Mariners blogs which were the most informative and funniest in sports. Blogs were great. They provided useful content, often from experts in a field—they could be both short form or long form, and through their comments section they provided opportunities for interaction, if one wanted that.

Social media platforms, especially Twitter, destroyed the blogosphere and so we resented them and to a certain extent resisted them. And yet it was the Seattle Mariners which compelled us to join Twitter, a few years after it became popular. The continuously losing, perpetually inept Mariners have been the cause of so many of our missteps, so much of our misery. If they had not been formed in 1977, if we had not attended their first game ever, it’s possible we would today be an unstoppable force of nature, a relentless model of happiness. But we digress. We joined Twitter when we realized that was the best and fastest way to learn of Mariners news once the blogosphere died an unhappy death. Eventually we embraced Twitter. We appear to have a different experience than many on the platform—we use it to follow not only the Mariners but the NBA, as well as a variety of international and economic sources. So we avoid most of the craziness and putridness of the platform.

But now it too appears to be dying. The final straw being Elon Musk limiting the number of posts one can read, driving even more useful sources of information away (doesn’t seem like a sound business plan to us—we’re cancelling our trip to Mars with Musk). In the modern era, information structures/platforms appear to have a seven to ten year life span. We don’t know what comes next but we expect the Mariners will lead us into whatever dark alley emerges. And we lead you into who has negative views of their economy, whether India is becoming a manufacturing giant, and what we were right about on China. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, named as an alternate to the international information and data all star game.

Speaking of the all star games, we’re attending baseball’s version next week, along with all the other festivities and activities surrounding it, all of which take place in our fair city of Seattle. It’s possible this will mean no INTN next week…or like Logan Gilbert, perhaps we will pitch a complete game. Be ready for either possibility.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

How Do You View the Economy?

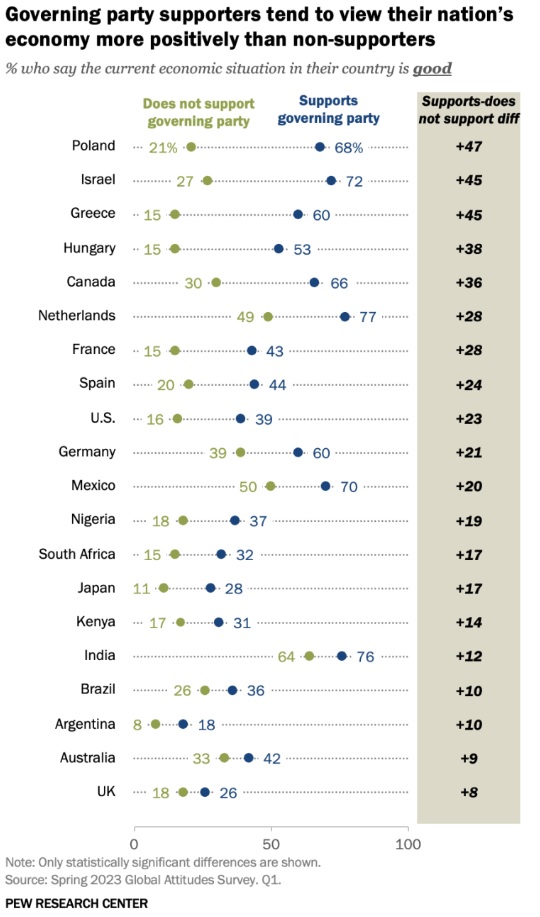

Rarely have we less understood the U.S. economy than we do today. Not only do we not pretend to understand the reasons for what has happened in the economy the last year, we have very little grasp on what will come the next 12 months. So we view all polling on views of the economy with some trepidation, projecting our own uncertainty. Nonetheless, Pew Global’s survey of folks in 24 countries on whether their country’s economy is good or bad is interesting. In 74 percent of the countries surveyed, respondents rate their country’s economic situation as bad, as you can see in Pew’s chart below. “Only in India, Indonesia, Mexico and the Netherlands do majorities call their economic situation good.” We note three of these four countries have likely benefitted from countries diversifying their supply chains outside of China though that is unlikely the main reason for their economic success. It’s also worth noting that “in 20 of the surveyed countries, those who support the governing party or parties are much more likely than those who do not to offer a positive assessment of their economy.” Our minds are more like sports fans than economists.

India Becoming Manufacturing Giant?

Speaking of India and supply chains, the below graph from Noah Smith is more evidence for our statement above that its economy is benefitting from the diversification of supply chains outside of China. Electronics exports are surging there. Apple, of course, has made announcements over the last few years that it is manufacturing more iPhones and other equipment in India. Lots of other companies are doing this as well. Manufacturing already accounts for 16 percent of Indian GDP. Will that rise to 25 percent in the coming years (about the same as South Korea and China)? With so many countries now utilizing industrial policy, including the United States, how will that affect the rise of India and other countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam (and a variety of African countries)? The world economy is likely to look very different in the coming years.

China Corner: We Were Right!*

For half a decade we’ve been saying that China’s future economic growth will be more like the United States and Europe than its past high growth. Until the last year or so most people did not believe that. U.S. financial firms, who because they want to be successful in the China market have to say things are going swimmingly there, continued to project high growth for China. But so did many others, including economists, long-time China experts and others. But as you can see in the chart below from the Financial Times, China’s economy is now “forecast to grow not much faster than other large economies.” The Financial Times uses the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States) as a comparison. When looking at that graph, remember it is using official Chinese government GDP numbers which are about as accurate as a statement by Elon Musk on Twitter. All of this being said, we still expect a short-term bump in China’s economy as it continues to rebound from Covid. But mid and long term its economy will fare no better than the U.S., Europe and other such countries.