How should one celebrate holidays and special occasions nowadays? People place a high priority on these things as evidenced by the large increase in travel and gatherings during the American Thanksgiving/Christmas/New Year holidays that led to huge spikes in infections and deaths. We cherish these traditions so much we’re willing to die for them, literally. Coming up is Valentine’s Day. An acquaintance of ours lamented she and her husband could not find an Airbnb to celebrate both V’day and her birthday—they are all booked up she told us.

For some Americans, the Super Bowl is a quasi holiday, with large gatherings full of Doritos, guac and beer. Had our beloved Green Bay Packers not been unseated by the hated other Bay team, we might be tempted to celebrate ourselves. Of course, there are many other occasions to celebrate. Nations like to celebrate their founding, for example. In Challenging China, we noted that China had much to celebrate in October 2019—the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China—but that “we wouldn’t have celebrated by featuring a parade of nuclear-capable missiles, soldiers marching in lockstep, and interminably long speeches (we would have hired a band or DJ and mixed some cocktails)…”

But Taiwan is smarter than we are. They found a way to celebrate their national day that was even cooler than cocktails and DJs, and definitely better than long speeches. They commissioned a bunch of talented youth to perform an elaborate dance sequence captured in one continuous take to Janet Jackson’s and Missy Elliott’s Burnitup. Now that’s how you celebrate. And since it is in the ever underrated Taiwan, which controlled Covid-19 better than just about anyone, it’s also safe. To celebrate this week’s INTN, we do the Harlem Shuffle on how video games supplanted music for the youth cool factor, do the twist on whether the poor or rich work harder and cha cha to what drives China’s economy. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, still waiting to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate as your source for international information and data.

Video Games, The Cool Factor and Music

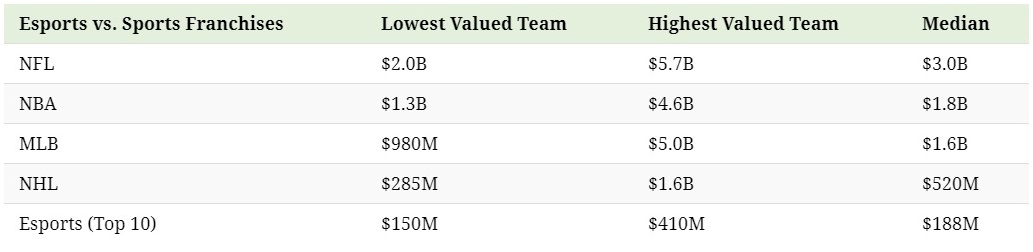

When I was younger I wondered what would be the new musical genre that I would be incapable of understanding and appreciating just like previous generations did not get the music of my youth. I can’t remember where I saw it now but someone recently wrote that video games are the music for today’s youth. It is in gaming that youth define themselves, rather than knowing and being into the coolest bands. And that could be true. Most people in my generation, including me, are not active video game players and don’t understand the gaming culture. We’ve written before about the growth of esports, and perhaps that is one manifestation of this new culture. Visual Capitalist recently did a breakdown of esports franchise values compared to traditional sports leagues. Although they have grown tremendously, their value is still smaller than almost all NFL, MLB and NBA teams as you see in the chart below. But, their values are growing and may surpass traditional sports teams as my generation and older generations walk into the great beyond. And did you know there are now over 50 universities in North America with varsity esports programs? “These programs offer full or partial scholarships to stand out high schoolers that are near the tops of ranked leaderboards.” We didn’t. And, of course, revenue for video games in general, esports or no, are more than film and music revenue combined. Today, the equivalent of being into The Clash in 1978 is knowledge of some aspect of a video game—we can’t tell you which one because we are neither cool nor young, and that is as it should be.

The Poor Work More Than You and Me

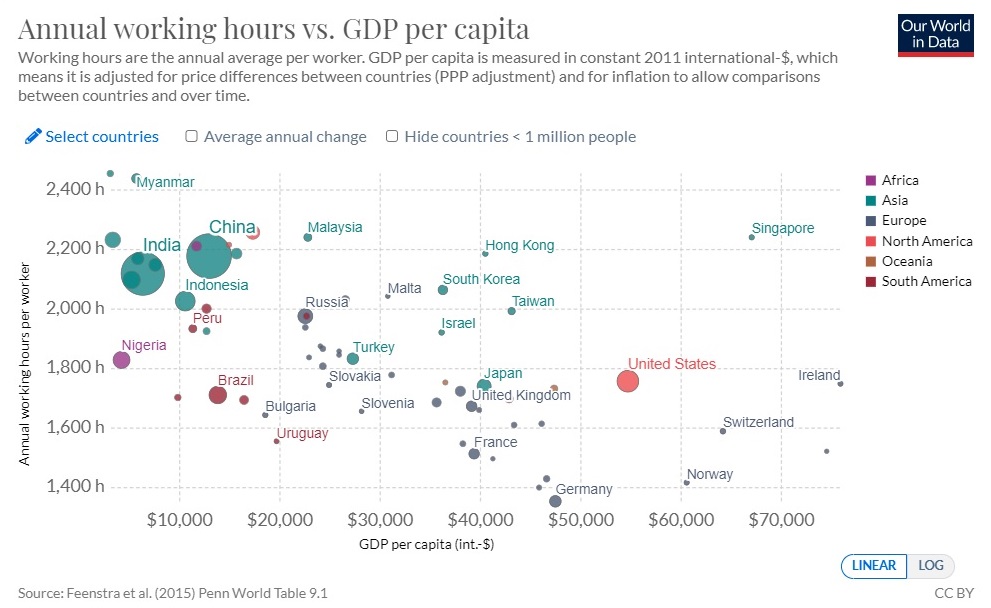

While shaving in the morning we often listen to NPR. Earlier this week they had a story about Blacks going back to farming and interviewed someone who returned to their Dad’s cotton farm to run it. While perhaps this was a charming human interest story, I’m not sure what this story told me about the larger world. There is no statistical trend of more agricultural workers. There are one-offs like this guy in Alabama but the economic progress of Blacks, or any other group, is not dependent on going back to farming. That’s because farming has become more productive with technological advances. The same is true for countries. People in poor countries work longer hours than those in rich countries, as you can see in the chart below. As OurWorldinData.com puts it, “The key driver of rising national incomes and decreasing working hours is productivity growth… This is because in richer countries workers are able to produce more with each hour of work, which translates into higher incomes and the ability to work less.” Note the countries in the top left of the chart—those who work long hours and have low GDP per capita—they are less developed countries such as Myanmar and Bangladesh. The poor in developing countries are not poor because they don’t work hard. Economic development in these countries and others are good for humanity, including by creating more voluntary leisure time.

China Corner: What Drives China’s Economy?

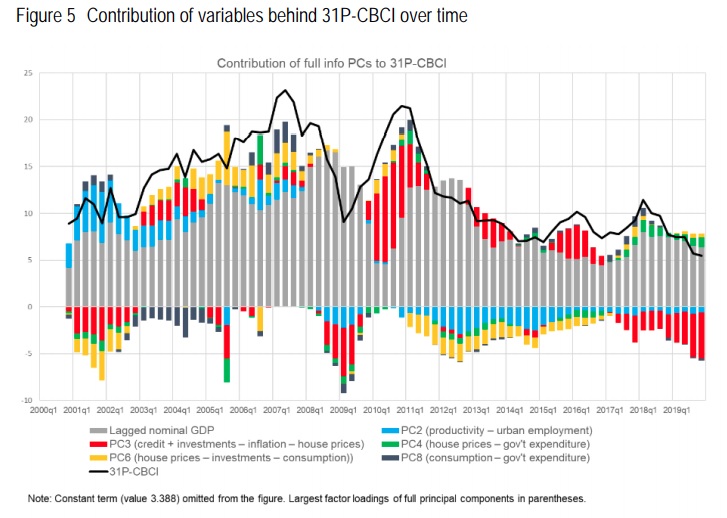

No sooner did we explain last week why China’s GDP growth is lower than they claim, than a new paper comes out explaining the components of pre-2020 GDP growth in China. Two researchers at the Bank of Finland assert that what drove GDP growth post 2010 is different than the previous drivers. “We show that during 1999–2010, aggregate growth was predominantly dependent on investments, internal migration and productivity of the urban workforce. After 2010, growth has been increasingly dependent on government expenditures, house prices and credit.” Eeva Kerola and Benoit Mojon looked at provincial GDP numbers, which unlike national GDP numbers, have shown some fluctuations over the years and so they consider the data more reliable. Remember that pre-Covid, China’s annual GDP growth was always 6 percent, a figure derived after China announced it wanted to double its GDP in 20 years. Regardless of growth rate, China now relies more on housing prices, credit and government expenditures to achieve GDP increases. The problem, as Kerola and Mojon see it, is that “For years now in China, indebtedness has continued to rise. Trying to reach the impressive goal of doubling real 2010 GDP by 2020 has required constant stimulus to the economy, with the result that debt has ballooned. Gross aggregate debt of the Chinese government, non-financial corporations and households is already close to 300% of GDP.” We’re not confident that China’s provincial GDP numbers are any more reliable than its national ones, fluctuations or no. But we do think this paper accurately reflects China’s current economic drivers. Challenging China details why China will no longer see high GDP growth rates in the future.