We are about two-thirds of the way through Deepti Kapoor’s novel, The Age of Vice. We picked it up both because we heard it was a page-turner and as part of our ongoing effort to understand India better. We have indeed tapped the screen quickly on our Kindle as Kapoor’s plot and characters captivate. Her book is often compared to The Godfather because of its depiction of a syndicate family in India. But what we think of most when reading Vice is Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. Not because of the style of the writing: there are not an abundance of exclamation marks or ornate phrasing or use of repeated words in the novel. But The Age of Vice, like Bonfire, is about a city. New Delhi is as much a character in the novel as New York was in Bonfire. And just as that novel from the 1980s is fixated on social status—as was Wolfe himself—so too does this theme resonate throughout The Age of Vice. Kapoor’s novel, like Wolfe’s, features characters from all levels of society. Plus, Kapoor, like Wolfe, is a journalist, and her reportorial techniques shine through the novel.

Wolfe once said, “fiction writers and nonfiction writers needed to leave the building and get out and take a look at this extraordinary country that we live in.” Kapoor most definitely has left the building to good effect, presenting her country, India, in its many complexities. Reading The Age of Vice also reveals how much our world has changed since the 1980s. Back then Wolfe could reasonably argue, as he often did, that he was writing about the most important city in the world, NYC. But now places like Delhi are more important as we hurtle headlong into the Asian Century, one that will be defined by the battle for cultural, economic and military supremacy between South and East Asia. As we continue turning pages, we stalk the billion-footed beast with stories of Chicken Littles, who will change the New World Order and China’s strengths. It’s this week’s International Need to Know, pining for Dong Phuong king cake in dark, rainy Seattle.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

Chicken Littles of Scarcity

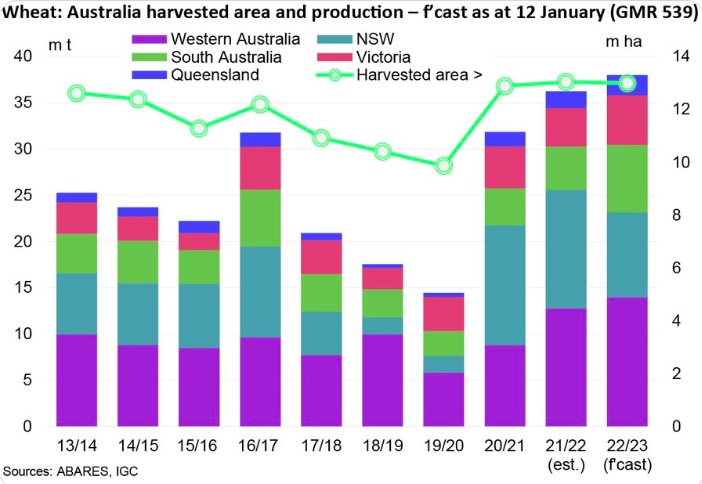

We humans, especially in the media-craving-eyeballs era of the early twenty-first century, excel at crying we are doomed. We especially are talented at saying that one thing or another that is needed for modern society is scarce. It’s usually not true. Take two examples. First, you may remember nearly a year ago being told that we were all doomed because Ukraine was such a large sower of wheat and would not be able to reap the much needed grain because of the war. Famines around the world would ensue as a result, it was predicted. Well, it turns out, according to the International Grains Council, that “world wheat production is forecast at a new all-time high.” This is thanks to record output from China, Russia and Australia (see Australia wheat chart below). So, eat bread and pasta without fear or guilt. Meanwhile, other chicken littles continue to cluck about so-called “rare earth” or “rare minerals.” We will either run out or be at the mercy of China where it is all mined. Except these materials aren’t particularly rare and can usually be found in many places. The example this time is Sweden where, according to the Washington Post (almost as reliable a source as the International Grains Council), “was discovered what is billed as Europe’s biggest deposit of rare earth minerals — a crucial component of electronics and clean energy technology.” Most things are not scarce or else easily substituted. If only chicken littles were more scarce.

Who Builds The New World Order?

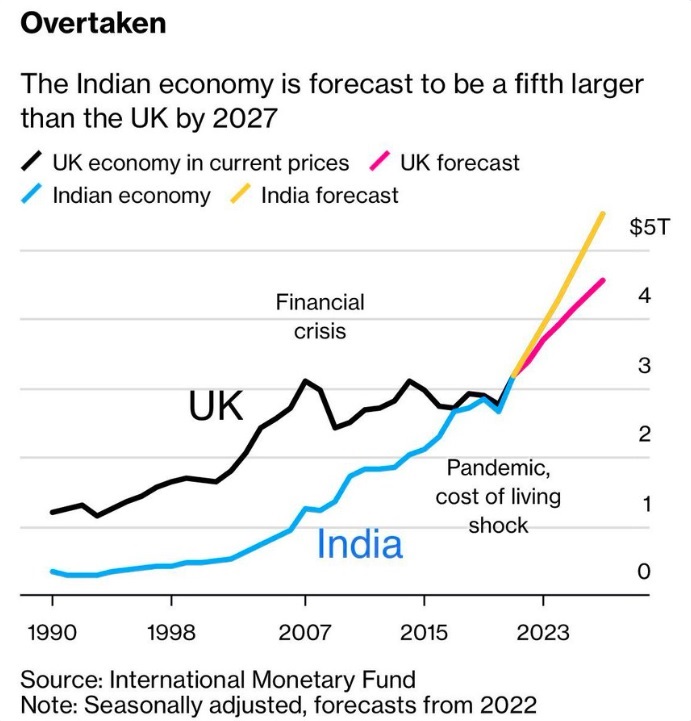

The rules-based, liberalized world order is dead. We said this at a Council on Foreign Relations meeting circa 2016 or 2017 and were roundly criticized for it. But we are an excellent world coroner. In our book Challenging China we described how China is trying to change the rules-based international order into one that will make the world safe for authoritarianism. We suggested ways to stop that. But, that doesn’t mean we think the order doesn’t need to change or that it won’t change. It’s not just China but many countries that want to see the rules-based order evolve, including the largest and soon likely to become more influential country, India. Prime Minister Narendra Mohdi speaking at the Voices of Global South Summit said:

We, the Global South, have the largest stakes in the future. Three-fourths of humanity live in our countries. We should also have an equivalent voice. Hence, as the eight-decades old model of global governance slowly changes, we should try to shape the emerging order.

Many mistakenly believe the rules-based liberal order was made solely by the United States only for the United States. The U.S. was the leader in creating that order but there were many architects. And most countries were beneficiaries of the order, including and especially China. A different set of countries, probably more diverse, will build the new order. India will almost certainly be one of those architects. Let’s hope, work to ensure, they reconstruct a liberalized rules-based order that makes the world safe for democracy and helps countries, especially developing ones, succeed.

China Corner: China’s Electric Strengths

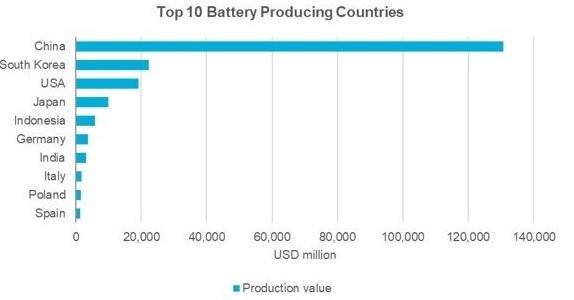

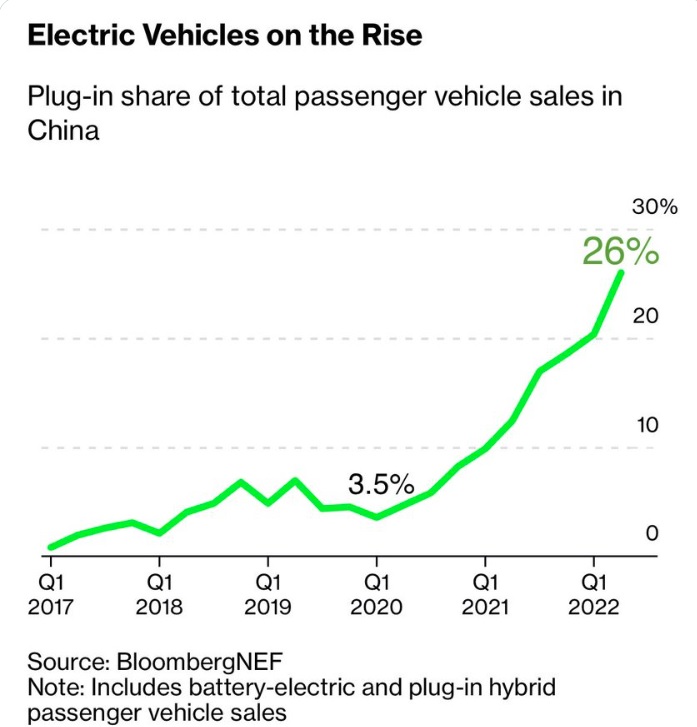

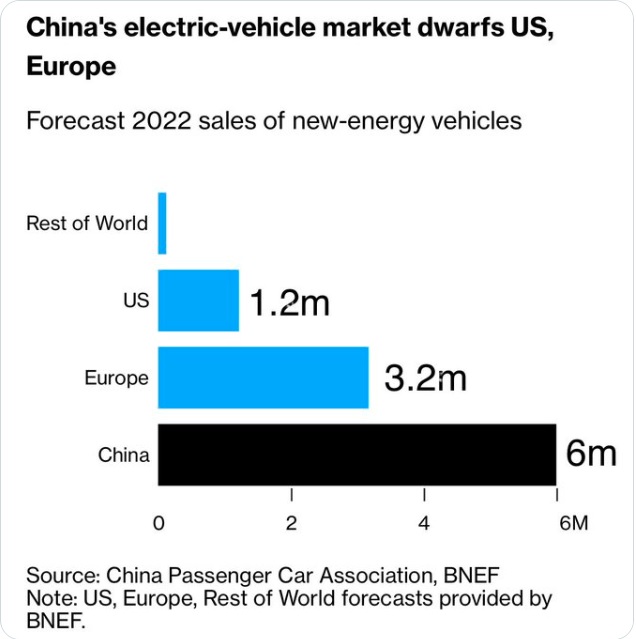

All systems have their strengths and weaknesses, except for Rite Aid, which is incompetent and evil and should be smothered in its own corporate pillow. China is a good example with all sorts of economic challenges, but also possessed of many strengths. Case in point is electric vehicles (EVs) and not coincidentally batteries. China is by far the leading manufacturer of batteries (see first chart below). It is also now the largest manufacturer of EVs. Over a quarter of new cars sold in China are now EVs (see second chart below). In fact, China’s EV market is larger than the rest of the world’s combined. Increasingly China is exporting cars, EVs to be specific. China’s auto exports to Europe have tripled since 2020 (the third chart below). If, as many people including INTN predict, the future of autos is electric, then China is perfectly positioned to dominate this industry in the coming decade. China has many challenges, including as was widely reported this week, demographic problems*. But all of its very real economic challenges do not mean that China won’t be important to, and in some areas dominant in, the global economy.

*All of the stories this week reporting that China’s population is decreasing for the first time since 1961 neglect to point out that there’s a good chance China’s population has been decreasing for the last four years and that its claim of 1.4 billion is possibly too large by a little over 100 million people. We can only understand China’s future if we understand China’s present.