The resignation of Harvard’s president, of which we have no opinion whatsoever, reminded us that when we were in college about six thousand years ago at Willamette University, where Harvard students couldn’t hold a candle to our intellect and glee competitions, we had a practice of inserting a fake citation in every single one of our papers. All of our footnotes were legit except for one, where just for kicks we’d make up a source or name of some publication or in some cases conjure up names of fake researchers. It’s the kind of thing we found funny at age 18, 19, 20 and 21. And maybe still do even today. Sometimes we’d attempt to make the citation realistic but often we would insert rather outlandish ones. Interestingly, we were never called on this by any of our professors. It didn’t matter whether it was English papers, history or social science, we had a fake footnote or reference in there somewhere.

The only exception might have been our senior mathematics seminar (though at this distant time our memory is uncertain). You can’t trust those wily mathematicians to not ferret out fakery and come after us like a rabid gang chasing after a proof of a Navier-Stokes equation. The entire Willamette math faculty did after all laugh out loud at our horrible handwriting when we presented a long complicated problem on the chalkboard during our senior seminar. Which is all to say we’ll never be president of Harvard, much to the relief of its students, faculty, staff and board, and much to the consternation of Yale. What we can say with complete confidence is that all of the stories below contain nothing but 100 percent certified sources, which means given how much we all get wrong in this crazy world, you should be very suspicious indeed.

But in honor of the artificial ordering of time, as people declare a new year, we depart from our usual format to step back and consider three of the seven most important countries in the world. Below you’ll find a quick assessment of their importance and at least two questions we should ask about them this year. The other four countries? They can go to hell.

Without further ado, here’s what you need to know.

India’s Century Beginning?

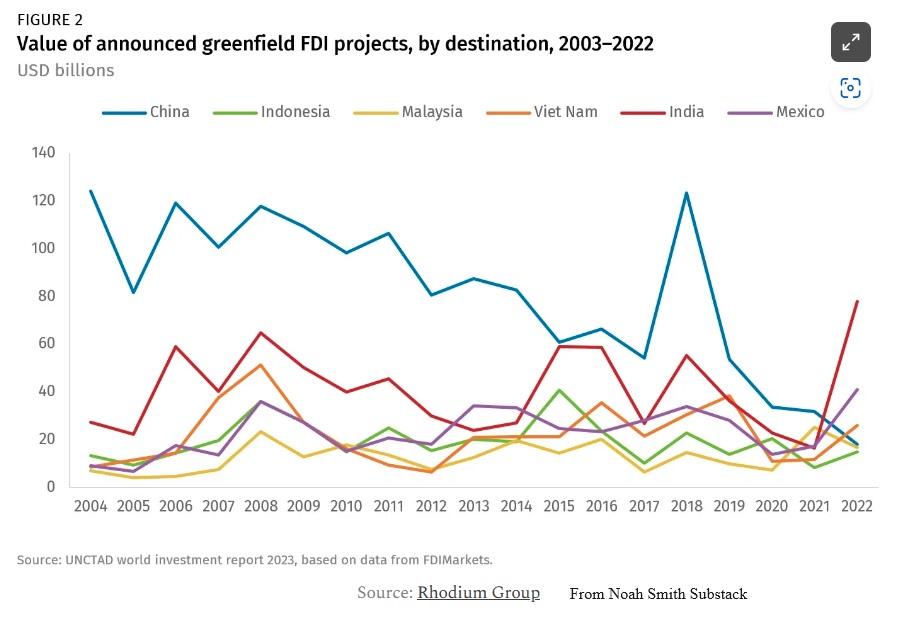

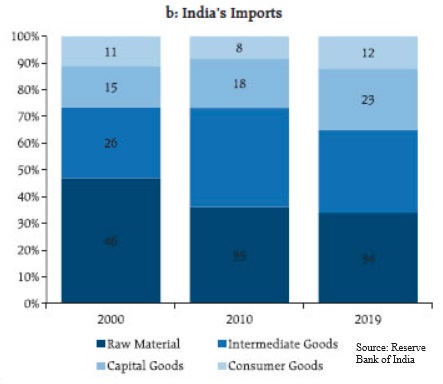

India is an easy one. It officially became the most populous country in the world last year.* But more important it continued to become a key part of global supply chains. As you can see in the first chart below, foreign direct investment has increasingly shifted towards India and away from China. Apple and other companies more often manufacture in India. In addition, India is now ranked ninth globally for foreign direct investment logistics projects. In the second chart below you can see what India is importing is changing as it becomes a location for manufacturing and supply chains with more intermediate and capital goods now being imported. Three big questions for India in 2024: a) will its role in global supply chains continue to grow? b) will Modi’s government restrict political liberalization? (It’s important to note India has elections this year); and c) how will India use its increasing influence around the world? India will undoubtedly want to change global institutions and what was once a liberal rules-based order. But it’s not clear what it’s vision for the world is.

*Likely it’s been larger than China for a number of years if we discount China’s official population figures.

As Vietnam Turns

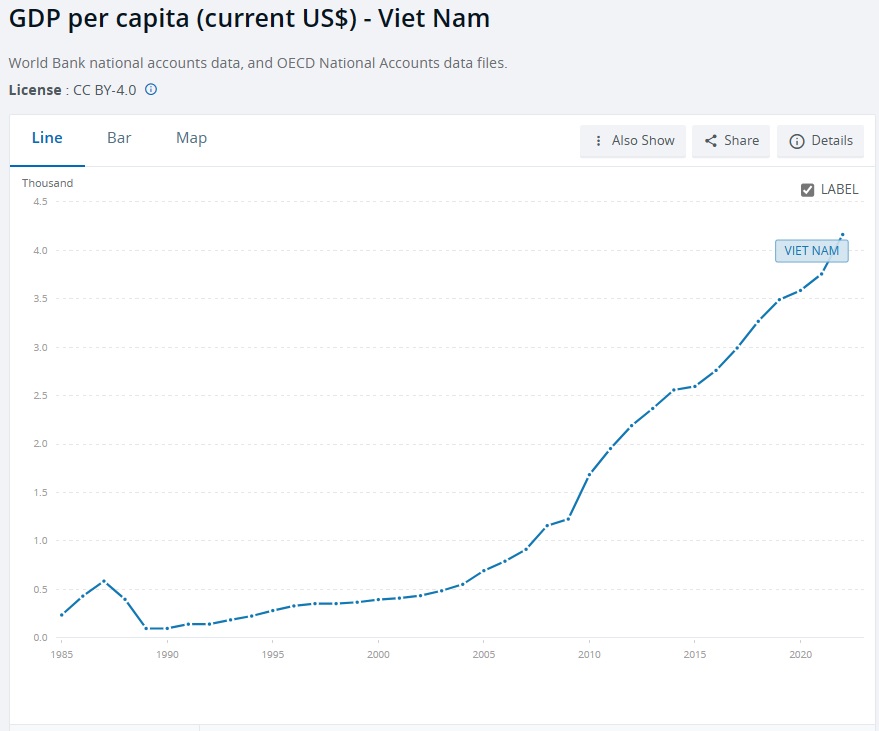

We list Vietnam here not just because we travel there at least once per year. Remember we wrote in Challenging China (published two years ago but much of it written in late 2019 and 2020) that Vietnam is one of the most important countries in the world because it can either follow the South Korea and Taiwan model of growing economically then liberalizing politically or it can take the new road China has trod: after growing economically becoming even more authoritarian. The $5000 GDP per capita level is often when countries start to deepen political liberalization. Vietnam likely finished 2023 with GDP per capita at $4600. That means, absent a recession, Vietnam will cross the $5000 level either in 2024 or 2025. Like India, Vietnam is increasingly an important hub of global supply chains. But like China, the communist government is cracking down on civil society in an effort to perpetuate its rule. Which road Vietnam chooses over the next few years will have ramifications for the fate of autocracy in our world. That’s the biggest question Vietnam faces. But related questions are will its economy grow at a rapid rate (it likely grew just over 5 percent in 2023)? How much more of the global supply chain can it absorb? And will it rise up the value chain (making higher value goods)?

China Corner: Myths and Mysteries

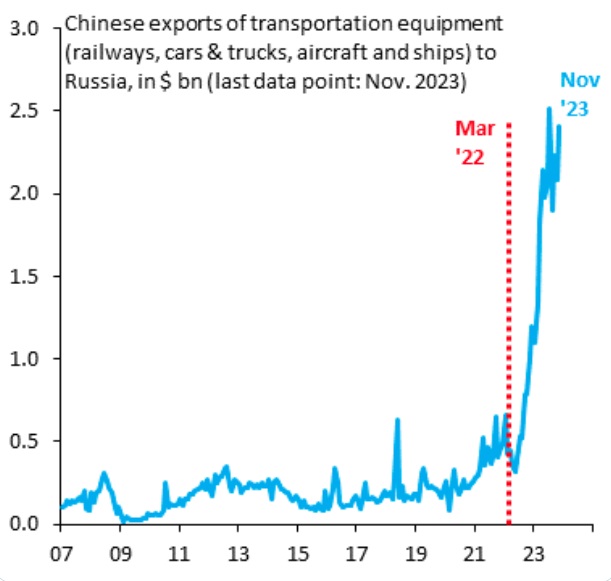

What? China is one of the seven most important countries in the world? Are you crazy? How can the second-largest economy in the world (first by purchasing power parity GDP), that is actively engaged in destroying the liberal world order, is increasingly aggressive in the South China Sea and continually threatens Taiwan be considered so important? The question answers itself. Few countries have more myths and mysteries than China. Outsiders and China itself has created many of these myths. China is increasingly mysterious because it is increasingly opaque—a much larger, much more economically successful North Korea. We predicted correctly in Challenging China that China’s economic growth would be low going forward, which at the time was controversial, so strong is the myth of China’s economy. One big question for China is how it navigates the economic challenges of high local debt, a popped real estate bubble and low household income share of GDP. Another big question is how Europe will react to an influx of subsidized Chinese electric vehicles flowing into its market? A third big question is what happens to the shoal in Philippine waters, and how will the U.S. and other Asian nations navigate the confrontation? Fourth, will the U.S. and Europe continue helping Ukraine as much as China is helping Russia? There are about 17 big questions for China but for now we’ll stick with those three.